Research and Evaluation team: Abdiaziz Ali, Silvia Kahihu, Ann Wanjiku, and Ken Lee

External collaborators: Claudia De Goyeneche, University of California, Berkeley

Sector: Education

Project type: Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT)

Location: Hargeisa, Somaliland

Sample: 1,272

Target group: Children aged 5 years

Project Overview

- Background

Early Childhood Development (ECD) in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) faces significant challenges. A staggering 61% of children under five in SSA fail to reach their full potential due to factors like poverty, malnutrition, and limited access to early learning opportunities (Neuman and Devercelli, 2012). In Somaliland, where primary education typically begins between the ages of six and eight, especially in resource-scarce rural areas, the situation is even more critical. Comprehensive data on Early Childhood Education (ECE) programmes is scarce, with most children missing out on preschool and enrolling directly into primary school between the ages of six and eight. These children often attend Quranic schools concurrently, which, while providing spiritual and moral education, do not prepare them for formal schooling as ECE programmes do (MoES education sector analysis, 2016).

The issue is more pronounced in rural areas, where educational resources are limited, and children are less likely to receive any form of schooling. The lack of comprehensive data on ECE in the region strains efforts to assess enrollment rates and demand for ECE services. According to UNICEF, access to ECE services in Somaliland is extremely limited, with an estimated enrollment rate as low as 5.7% for children in this age group (UNICEF, 2012). Despite the Ministry of Education Service's (MoES) efforts to promote ECE as a strategy for enhancing learning, the achievements have been minimal due to resource and technical challenges, as highlighted in the Joint Review Education Sector (JRES) 2018/19 Report.

While research on the impact of ECE programmes in Africa is limited, existing studies indicate positive effects on primary school enrollment, test scores, and cognitive skills (Ganimian et al., 2021). Beyond cognitive development, studies also emphasise the importance of social and emotional skills (Currie, 2001), parental investment (Attanasio et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2023), and parental decision-making (Dizon-Ross, 2019; Wang et al., 2023; Abdulkadiroğlu et al., 2020). Additionally, considerations such as cost-effectiveness, programme quality, and long-term impacts are crucial (Ganimian et al., 2021; Karoly, 2016; Gelber and Isen, 2013; Blimpo et al., 2022; Das et al., 2013; Rossin-Slater and Wüst, 2020).

This study aims to fill the knowledge gap by evaluating the effectiveness of ECE initiatives implemented in Hargeisa, Somaliland, by Pharo Foundation. Building on the positive outcomes observed in our initial ECE pilot study in Berbera, we are expanding our research to include multiple schools across Somaliland with a larger sample size. The findings will provide the national government with crucial insights to assess the feasibility of expanding this programme nationwide, particularly in regions where ECE has been limited. The long-term goal is to establish a nationwide ECE programme, funded by the Government of Somaliland and potentially supported by external donors, by 2030. The study's findings could significantly shape policy discussions and attract potential donors, given the documented impacts.

Our research employs a nine-month randomised controlled trial (RCT) from August 2023 to May 2024 in Hargeisa. The primary objective is to evaluate the programme’s impact on various domains of child development, including cognitive and social skills. Secondary objectives will explore potential effects on parental well-being, educational investment, and expectations. We will also estimate the demand for ECE programmes, considering the potential for parents to develop more positive beliefs about their children’s abilities after exposure to the programme (Dizon-Ross, 2019).

Specifically, we aim to answer the following primary questions:

- What is the impact of ECE on childhood development, as measured by the International Development and Early Learning Assessment (IDELA)?

- Which children benefit the most from ECE, considering heterogeneous treatment effects?

- What is the demand for ECE among parents?

- What are the economic implications of a national ECE programme?

II. Interventions

The Early Childhood Education (ECE) programme

Pharo Foundation has been running the Early Childhood Education (ECE) programme since 2016, aiming to increase access to quality ECE for children from poor to middle-income families by integrating it into the public education system. Over the years, the Foundation has established 14 ECE centres in Hargeisa's public schools, with a yearly capacity of 970 pupils. The programme has grown in popularity, leading to consistent oversubscription, as evidenced by 1,396 students registering for just 970 placements in 2022. To address this, the Foundation is implementing a randomised admissions procedure for its Hargeisa ECE programmes, which is considered the most equitable approach.

The programme operates 5 days a week for 4 hours per day, following daily structured learning sessions designed to stimulate child development through play and centre based activities. Each classroom holds up to 30 children and is staffed by one instructor. While enrollment is limited to children between 5 years, classrooms are mixed by gender. The primary language of instruction is Somali, the local language. The programme also includes off-site teacher training; provision of teaching and learning materials; and daily nutritional snacks.

The study unfolded across a single academic year, starting on August 5th, 2023, and concluding on May 18th, 2024 in all 14 ECE schools.

Information treatment - Update of beliefs

The information treatment (or “Good news message”) is designed to inform parents about their child’s strong performance on the IDELA assessment (i.e., being in the top 50% within their distribution ) and provide guidance on how to build upon those strengths at home. Key points include the child's exceptional performance on the IDELA assessment. We encourage parent engagement by asking parents to share examples of their child demonstrating these skills at home. Additionally, we offer activity suggestions to provide parents with specific activities to support their child's development in reading, maths, and shape recognition. For children who did not score above the median, we provide a neutral message in addition to activity suggestions.

III. Research design and methodology

Eligible children were randomly assigned to either the treatment group (receiving the ECE

programme) or the control group (not receiving the programme) using a computer-generated process conducted within our office. In the case of twins, only one was included in the randomization process. If one twin was assigned to the programme, the other was automatically enrolled as well. A total of 1,511 children were registered at baseline. Of these, 894 attended the programme (nT) while 617 were not selected (nC). At the endline, 1,272 children were tracked, including 789 who had attended the programme (nT) and 543 who had not (nC). During registration, at baseline and endline, we gathered detailed information about the child and their family, including demographics, vaccination records, sibling details, and prior ECE attendance. The registration form also collected personal and occupational data for the primary caregiver and, if applicable, the father or guardian and other household characteristics e.g., the respondent’s relationship to the child, family composition, and asset ownership. Biometric measurements were collected at both baseline and endline to assess the physical growth and development of the children. These measurements included height, weight, and mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC).

To assess the children’s early learning and development, we collected data at the beginning (baseline) and end (endline) of the study using the IDELA assessment tool – a rigorous global tool that measures a wide range of skills, including motor development, early language and literacy, numeracy, problem-solving, and socio-emotional skills. By using a standardised instrument like IDELA, which is widely used around the world (https://idelanetwork.org/), we gain the ability to compare our findings on child development with research conducted in other countries.

The primary caregiver survey collected detailed data on household characteristics, the child’s home environment, daily routine, and caregiver involvement. The survey further explored caregiver well-being through the CES-D scale and assessed caregiver stress related to child nutrition. Additionally, it addressed maternal and child health by inquiring about pregnancy, breastfeeding, sleep patterns, and emotional development. The endline survey updated this data, adding modules on cash transfers, to establish a baseline for the willingness-to-pay analysis, labour supply to capture changes in employment status since the baseline, parental investment behaviours, and parental educational aspirations for their child. To evaluate programme impact and inform future programme design, the endline survey included specific modules for the treatment and control groups. The control group responded to questions about attendance in other early childhood education programmes during the past academic year. For both groups, inquiries about future educational plans and desired characteristics of the next educational level were included.

In August 2024, we conducted an additional follow-up survey with parents to explore the demand for Early Childhood Education (ECE) and the economic implications of a national ECE programme. This survey included two key modules. The first, a Willingness-to-Pay (WTP) module, estimated parental demand for ECE by presenting participants with a hypothetical scenario in which their child either attends the ECE programme for a year or receives monthly cash transfers for a year. The second module, an information treatment, provided parents with details about their child’s performance on the IDELA test, either before or after the WTP questions, to assess how perceptions of their child's abilities influence demand for ECE. The survey also included additional components, such as data on social desirability using the Marlowe-Crowne Social Desirability Scale.

IV. Results

We present a highly preliminary analysis focused on checking the baseline balance between treatment and control groups and estimating the impact of ECE on key outcomes. Robustness checks and an in-depth analysis of all survey outcomes are currently underway, with results forthcoming.

Baseline characteristics are largely balanced between treatment and control groups, with only a few minor differences. There are no significant differences in child characteristics (such as sex and age), father's characteristics, or the child's IDELA test scores. However, we observed slight variations in mothers' and household characteristics. For instance, while two-thirds of mothers in the control and treatment groups had not attended primary school, the majority (~68%) reported being literate. In terms of household characteristics, comparison households were more likely to own motorcycles, whereas treatment households had a higher likelihood of having electricity. Despite these differences, there are no significant variations in overall income or ownership of other assets, ensuring that the comparability of the groups remains intact.

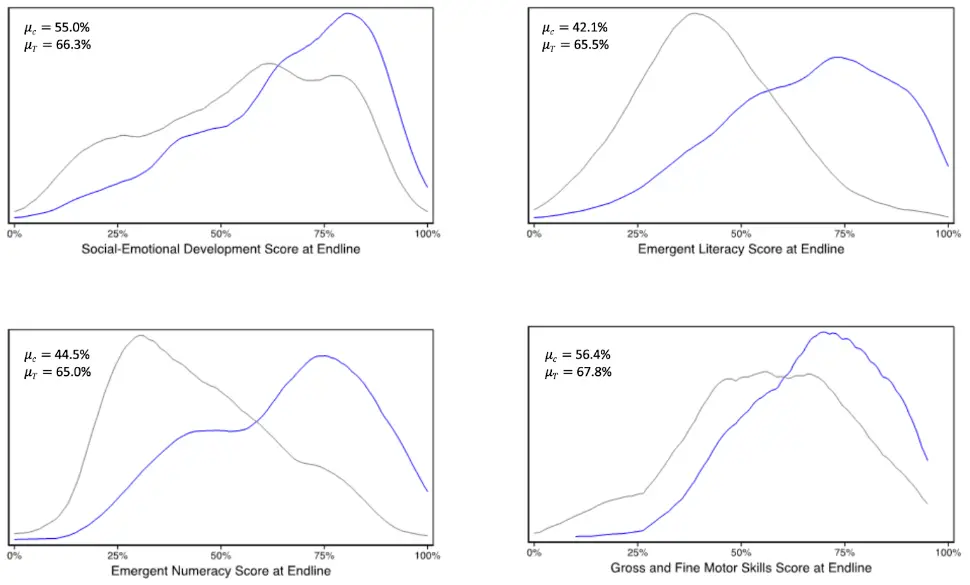

We estimate a large and statistically significant impact of the Hargeisa ECE programme on IDELA measures. Relative to the comparison group, treatment kids demonstrated significant improvements across all domains with the largest gains occurring along the emergent numeracy and emergent literacy dimensions.

Approximately 60% of control children were enrolled in alternative schools (e.g., Grade 1, madrassas). These control kids also showed significant improvements in maths and literacy over their pure control peers, indicating positive learning outcomes from less structured or early learning experiences.

Despite improvements in control kids, their performance still lagged behind Pharo ECE kids. This disparity may be due to lower quality of education in Grade 1 or incorrect age-grade placement. Our future research agenda includes investigating these potential causes.

Figure 1: Standardised scores of treatment and control kids